Frequently, in media coverage and legal articles, a defendant, whose case has generated publicity, will be said to face “20 years in prison on each count” or “a total of 35 years, or infinite variations of some multi-decade term.” In the federal sentencing system, it is important to differentiate between three specific concepts. First: The statutory maximum punishment for each offense charged. Second: The type of sentence which is a likely sentence under the United States Sentencing Guidelines, which were enacted in 1987, but which were substantially checked in their authority by a Supreme Court decision in 2005. Third: The existence or non-existence of a plea agreement, and the specific type and contents of such an agreement. Within the plea agreement area, a defendant's “acceptance of responsibility” and any potential for a government motion for downward departure are important factors as well.

Statutory Maximum Punishment

Each federal offense carries with it an upper limit of punishment in terms of the time in prison a defendant could receive for each offense of conviction. For example, if a defendant is charged with an offense which carries a maximum of five years in prison, then the most the defendant could receive for one conviction on that offense is five years. If the defendant is charged with 10 separate counts of a violation, which carries the potential for five years each, then the most a defendant could receive, if convicted of all 10 counts, would be 50 years. As a practical matter, the statutory maximum punishment a defendant faces in a particular case is often largely irrelevant, for reasons we will now explore.

The Guidelines

Until 1987, federal judges had wide latitude in sentencing defendants who came before them. Sentences varied widely in range from lengthy periods of incarceration, in some cases, to probation in other cases. Whether accurate or not, the perception was that white collar defendants frequently received probation or other lenient sentences, particularly if they had no prior criminal history.

This all changed in 1987 when Congress passed the “Federal Sentencing Guidelines.” Although labeled “Guidelines,” the Sentencing Guidelines turned out to be more like mandatory regulations. The idea was that sentences would be imposed based upon fact patterns that would be predicted in the typical or “heartland” case and the Guidelines would, for the most part, impose uniformity among the 96 federal districts in the United States.

Sentences did increase under the Guidelines regime and judges had little discretion to deviate from the Guidelines. However, in United States v. Booker, 543 U.S. 220 (2005), the United States Supreme Court held that the Guidelines were not mandatory and judges gradually, as Booker's impact became more and more clear, have become more comfortable in deviating from the otherwise applicable Guideline range. A judge can impose a more or less severe sentence. While still highly important, the “Guidelines sentence” is no longer the end of the calculus, as was the case from 1987 until 2005, in federal criminal cases.

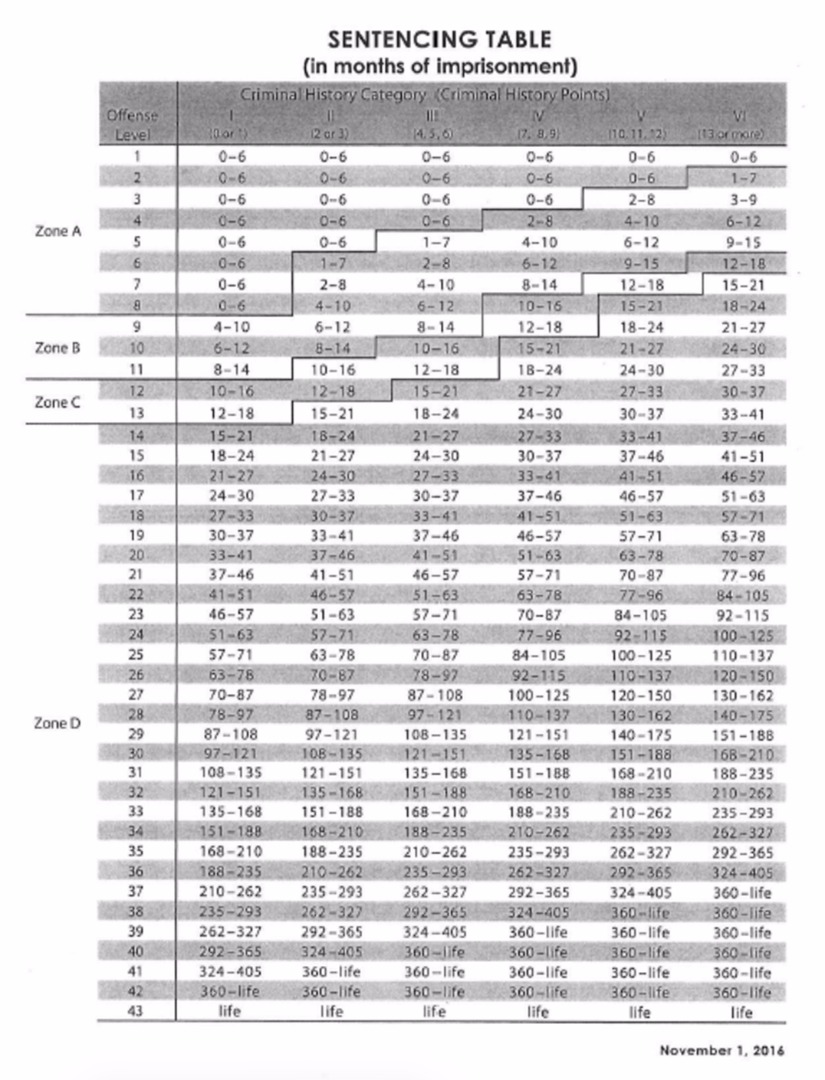

The Guidelines calculation begins with a determination of an offense level. Each federal crime can be found within the Guidelines and each offense has a beginning “offense level.” Various factors can increase the offense level and in white collar cases, those factors are basically the amount of money involved, the degree of sophistication and manipulation involved and the financial harm to institutions or individuals. Most white collar defendants have no significant criminal history so it is fairly uncommon to have anyone who is not at category one, the lowest offender level. The following chart is the mechanical way a sentence is calculated under the Guidelines once the offense level is established:1

______________________

1. A future article will illustrate the rather complex offense level calculation process under the Guidelines.

A person is not eligible for probation unless they are in either Zone A or Zone B. If the person is in Zone C, then some form of probation may be authorized within certain restrictions. If a defendant is in Zone D, then the defendant is not eligible for probation, absent a “downward departure” (within the framework of the Guidelines) or a “variance” (under the post-Booker/post-2005 “advisory” Guidelines). The lower number in each offense level is the minimum amount of confinement in months of imprisonment that the person could receive.

Plea Agreements

Under the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, there are three types of plea agreements:

1. Agreement not to bring or dismiss certain charges

The first plea agreement, under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 11(c)(1)(A), is an agreement not to bring certain charges or to drop charges. Although technically the judge is required to agree to this type of a plea agreement, it is almost unheard of for a judge not to go along with a (c)(1)(A) agreement. This type of agreement is frequently seen in complex white collar situations where a defendant will be given a choice concerning whether to plea to one or two offenses which may effectively “cap” the defendant's criminal exposure. For example, in a complex white collar case with large loss amounts, a defendant would be facing years of prison under the Guidelines. However, if a prosecutor brings a simple conspiracy count, under 18 U.S. Code §371, a false statement count under 18 U.S. 1001, or a “tax perjury” count under 26 U.S. Code 7206, then a defendant would face a maximum sentence of either five years under the first two statutes cited or three years under the tax perjury charge. If the prosecution agreed to only bring that one charge, or to only have that one charge standing after all the others were dismissed, then the defendant's maximum custodial time would be limited to the statutory maximum for whatever offense to which the defendant pled guilty, regardless of the sentence called for by the Guidelines.

2. Recommended sentence

The next type of plea agreement is under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 11(c)(1)(B). This is a recommendation by the Government for a particular sentence. Sometimes a plea under this particular provision of the rule will contain an agreement as to what the Government and the defendant agree is an appropriate guideline calculation and offense level. However, neither the recommendation nor any agreement on guidelines level or offense level is binding on the court. Although most judges will follow a Government recommendation in most cases, it is not unheard of at all for a judge not to follow a Government recommendation and sometimes to impose a more severe sentence and sometimes to impose a less severe sentence.

3. Binding plea agreement

Finally, under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 11(c)(1)(C), the parties can agree to what is known as a “binding” plea agreement. This is somewhat unusual in federal practice, but I have been involved personally in cases with this type of plea agreement in the Northern District of Alabama from time to time. The central characteristic of a binding plea agreement is that it means what it says in the sense that it is binding upon the Court, if the Court accepts the agreement. The Court has the power to reject the agreement in its entirety and can do so and tell the parties to start negotiations anew or set the case for trial. However, if the judge accepts the agreement, and allows the case to go forward after taking the defendant's plea, then the plea agreement is binding on the Court and whatever sentence has been agreed to between the parties must be implemented by the Court. Some judges are reluctant to accept these types of agreements, due to concerns over the impropriety of the Judicial Branch being required to accept a sentence agreed to by the Executive Branch. However, in my experience, judges will accept binding plea agreements if they believe the underlying result is not an unreasonable one.

4. “Acceptance of responsibility” / motions for downward departure

“Acceptance of Responsibility” is a technical term under the Guidelines which generally has the effect of lowering, by two or three offense levels, a defendant's total offense level under the Guideline calculations. Acceptance of responsibility credit can be given regardless of whether a defendant has “cooperated” with the Government and is usually given if the defendant signals a willingness to plead guilty in time for the Government to avoid the time and expense of preparing for trial. Different judges have different standards for how narrow that window is but, in general, as long as a defendant does not enter a plea on the day trial is to start, judges are normally willing to give credit for acceptance of responsibility. Depending on the offense level, acceptance of responsibility can be a valuable credit to receive, particularly if it can get a defendant into a zone where he is eligible for probation.

Motions for downward departure, on the other hand, are typically made under §5K.1of the Guidelines and are known among the federal criminal bar as “5K motions.” These motions almost always require that the defendant provide “substantial assistance” to the Government in cooperating with the Government's investigation, often by testifying or agreeing to testify against other persons involved in their activities. One thing to keep in mind about a 5K motion is that the Court is not bound by the Government's recommendation. In other words, if a defendant was facing a 60-month sentence under the Guidelines and the Government made a 5K motion and asked the judge to impose a three-year sentence, the judge could impose any sentence at all -- even including probation -- because the Government has “opened the door” to allow the judge to exercise discretion in sentencing. On the other hand, the judge could impose a more severe sentence than requested in the Government's §5K1.1 motion, or even deny the motion entirely.

Conclusion

When evaluating or monitoring a case, remember to avoid the temptation to simply conclude that the statutory maximum is controlling or even (materially as opposed to theoretically) relevant. The Guidelines remain highly influential in federal sentencing so the “likely sentence” called for by the now advisory Guidelines remains extremely important. Since the Guidelines retain such a significant role in federal sentencing, and because a huge number of cases are resolved by plea agreements, always try and determine the existence and type of plea agreement. If one exists, then is it an agreement to dismiss or not bring certain charges; an agreement for a recommended sentence; or an agreement for a definite, binding sentence? Under each of the first two categories, a motion for downward departure and acceptance of responsibility may have a dramatic impact on the ultimate sentence imposed. However, under a binding plea agreement, such an impact would be minimal. Each situation has to be evaluated with all of the three calculations discussed earlier: (a) statutory maximum for all counts charged; (b) likely sentence called for by the advisory Guidelines; and (c) existence of and specific type of plea agreement.